The Politics of Vision Essays on Nineteenthcentury Art and Society Pdf

Arising out of the rebellious mood at the start of the twentieth century, modernism was a radical approach that yearned to revitalize the way mod civilisation viewed life, art, politics, and scientific discipline. This rebellious attitude that flourished between 1900 and 1930 had, every bit its footing, the rejection of European culture for having go too corrupt, conceited and lethargic, ailing because it was spring by the artificialities of a society that was too preoccupied with epitome and too scared of change. This dissatisfaction with the moral bankruptcy of everything European led modern thinkers and artists to explore other alternatives, especially archaic cultures. For the Establishment, the result would be cataclysmic; the new emerging culture would undermine tradition and authority in the hopes of transforming contemporary lodge.

The first characteristic associated with modernism is nihilism, the rejection of all religious and moral principles as the only means of obtaining social progress. In other words, the modernists repudiated the moral codes of the lodge in which they were living in. The reason that they did so was non necessarily because they did not believe in God, although there was a great bulk of them who were atheists, or that they experienced great doubt about the meaninglessness of life. Rather, their rejection of conventional morality was based on its arbitrariness, its conformity and its exertion of control over human feelings. In other words, the rules of acquit were a restrictive and limiting force over the man spirit. The modernists believed that for an individual to experience whole and a contributor to the re-vitalization of the social process, he or she needed to be costless of all the encumbering baggage of hundreds of years of hypocrisy

The rejection of moral and religious principles was compounded by the repudiation of all systems of behavior, whether in the arts, politics, sciences or philosophy. Doubt was not necessarily the most pregnant reason why this questioning took place. One of the causes of this iconoclasm was the fact that early 20th-century civilization was literally re-inventing itself on a daily basis. With so many scientific discoveries and technological innovations taking place, the world was changing and then chop-chop that culture had to re-define itself constantly in order to go along pace with modernity and non appear anachronistic. By the fourth dimension a new scientific or philosophical organisation or artistic style had institute acceptance, each was soon afterward questioned and discarded for an fifty-fifty newer one. Another reason for this fickleness was the fact that people felt a tremendous creative energy always looming in the background equally if to announce the nascence of some new invention or theory.

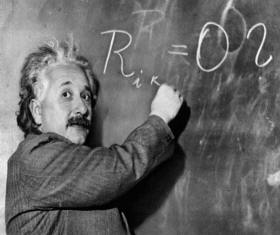

This mimetic tradition had originated style back in ancient Greece, had been perfected during the Renaissance, and had institute prominence during the nineteenth-century. But for modern artists this old standard was too limiting and did non reflect the way that life was now existence experienced. Freud and Einstein had radically changed perception of reality. Freud had asked us to look inwardly into a personal globe that had previously been repressed, and Einstein taught us that relativity was everything. And, thus, new artistic forms had to be plant that expressed this new subjectivity. Artists countered with works that were so personal that they distorted the natural appearance of things and with reason. Each private piece of work begged to be judged as a self-sufficient unit which obeyed its own internal laws and its ain internal logic, thereby attaining its own individual character. No more conventional cookie-cutter forms to exist superimposed on human expression

It is that exploration of what is underneath the surface that the modernists were so smashing virtually, and what better manner to exercise so than to scrutinize human being's real aspirations, feelings, and actions. What was revealed was a new honesty in this portrayal: disintegration, madness, suicide, sexual depravity, impotence, morbidity, deception. Many would assail this portrayal every bit morally degenerate; the modernists, on the other paw, would defend themselves by calling it liberating.

Ironically, the modernist portrayal of man nature takes place within the context of the city rather than in nature, where it had occurred during the entire 19th-century. At the beginning of the 19th-century, the romantics had idealized nature as evidence of the transcendent beingness of God; towards the end of the century, it became a symbol of chaotic, random being. For the modernists, nature becomes irrelevant and laissez passer�, for the city supersedes nature equally the life forcefulness. Why would the modernists shift their interest from nature and unto the city? The first reason is an obvious 1. This is the fourth dimension when and so many left the countryside to brand their fortunes in the city, the new capital of civilisation and technology, the new artificial paradise. Simply more chiefly, the city is the place where man is dehumanized by so many degenerate forces. Thus, the city becomes the locus where modern human is microscopically focused on and dissected. In the last assay, the city becomes a "cruel devourer", a cemetery for lost souls.

The year 1900 ushered a new era that changed the way that reality was perceived and portrayed. Years later this revolutionary new catamenia would come to be known as modernism and would forever be defined as a time when artists and thinkers rebelled confronting every believable doctrine that was widely accepted by the Establishment, whether in the arts, scientific discipline, medicine, philosophy, etc. Although modernism would be brusque-lived, from 1900 to 1930, we are still reeling from its influences sixty-five years later.

How was modernism such a radical departure from what had preceded it in the past? The modernists were militant well-nigh distancing themselves from every traditional idea that had been held sacred by Western civilization, and possibly we can even go and so far as to refer to them equally intellectual anarchists in their willingness to vandalize annihilation connected to the established society. In order to better empathise this modernist iconoclasm, let's go back in time to explore how and why the homo mural was changing then rapidly.

By 1900 the globe was a bustling place transformed by all of the new discoveries, inventions and technological achievements that were beingness thrust on culture: electricity, the combustion engine, the incandescent lite bulb, the machine, the airplane, radio, X-rays, fertilizers and so along. These innovations revolutionized the world in two distinct ways. For one, they created an optimistic aureola of a worldly paradise, of a new technology that was to reshape human being into moral perfection. In other words, technology became a new religious cult that held the key to a new utopian dream that would transform the very nature of man. Secondly, the new engineering science quickened the pace through which people experienced life on a day to day basis. For instance, the innovations in the field of transportation and communication accelerated the daily life of the individual. Whereas in the past, a person'southward life was circumscribed by the lack of mechanical resources available, a person could now expand the scope of daily activities through the new liberating power of the machine. Man now became literally energized past all of these scientific and technological innovations and, more of import, felt a rush emanating from the feeling that he was invincible, that in that location was no stopping him.

Modernity, even so, was not just shaped by this new applied science. Several philosophical theoreticians were to modify the way that modernistic man perceives the external earth, particularly in their refutation of the Newtonian principle that reality was an absolute, unquestionable entity divorced from those observing it. The first to do so was F. H. Bradley, who considered that the human being mind is a more than fundamental characteristic of the universe than matter and that its purpose is to search for truth. His about ambitious work, Appearance and Reality: A Metaphysical Essay (1893), introduced the concept that an object in reality can have no accented contours but varies from the bending from which it is seen. Thus Bradley defines the identity of a things as the view the onlooker takes of it. The event of this work was to encourage rather than dispel dubiousness. In ane of the nigh seminal works of this century, "On the Electrodynamics of Moving Bodies," Albert Einstein's theory of relativity held that, if, for all frames of reference, the speed of lite is constant and if all natural laws are the same, and then both time and move are found to be relative to the observer. In other words, there is no such thing as universal time and thus experience runs very differently from human to human being. Alfred Whitehead was some other who revised the ideas of time, space and motion equally the basis of human being's perception of the external world. He viewed reality every bit living geometry and believed in the essential relevance of every object to all other objects: "all entities or factors in the universe are essentially relevant to each other's existence since every entity involves an infinite array of perspectives." For all of these thinkers, subjectivity was now the primary focus.

Several psychological theoreticians were to also fundamentally alter the manner that modern man viewed his own internal reality, an unexplored heart of darkness. Sigmund Freud was the kickoff to gaze inwardly and to detect a world within where dynamic, often warring forces shape the private's psyche and personality. To explicate this internal world within each of united states of america, he adult a complex theory of the unconscious that illustrated the importance of unconscious motivation in behavior and the proposition that psychological events tin get on outside of conscious awareness. And then, co-ordinate to Freud, fantasies, dreams, and slips of the tongue are outward manifestations of unconscious motives. Furthermore, in explaining the development of personality, Freud expanded man'southward definition of sexuality to include oral, anal, and other bodily sensations. Thus his legacy to the mod world was to betrayal a darker side of human being that had been hidden from view by the hypocrisy of 19th- century order.

The French philosopher Henry Bergson was also to turn his gaze to the unconscious to explore the nature of memory as experienced in the present moment. Bergson's Time and the Free Will was an endeavour to found the notion of duration, or lived time, as opposed to what he viewed as the spatialized formulation of time measured past the clock and commonly known as chronological time. According to Bergson, states of conscious memory permeate i another in storage within the unconscious, in the same way that "oldie-goldies" are stored in a juke-box. A sense impression, such as whiff of cologne or the taste of sweet tater pie, might trigger consciousness to recall i of these memories, much like a money will cause the record of your choice to play. Once the submerged memory resurfaces in the conscious mind, the self becomes suspended, there might exist a spontaneous flash of intuition almost the past, and just maybe, this insight will translate into some kind of realization of the present moment. In fact, isn't this what we do when we listen to an former vocal, forget the present, re-experience the past, and, so, all of a sudden, apply it all to our lives in the present? And thus, intuition leads to knowledge.

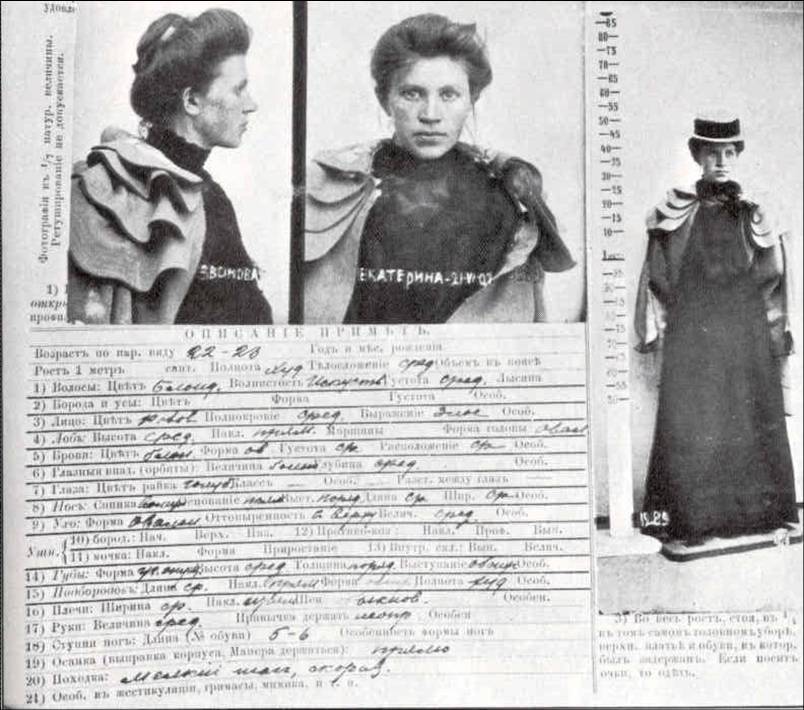

Politics and the economic system would besides transform the way that modern man looked at himself and the world in which he lived. Scientific discipline and technology were radically changing the means of production. Whereas in the past, a worker became involved in product from showtime to end, by 1900 he had get a mere cog in the product line, making an insignificant contribution. Thus, sectionalization of labor made him feel fragmented, alienated not only from the residue of gild merely from himself. One of the effects of this fragmentation was the consolidation of workers into political parties that threatened the upper classes. And, thus, the new political idealism that was to culminate in the Russian Revolution that swept through Europe.

Source: https://www.mdc.edu/wolfson/academic/artsletters/art_philosophy/humanities/history_of_modernism.htm

Post a Comment for "The Politics of Vision Essays on Nineteenthcentury Art and Society Pdf"